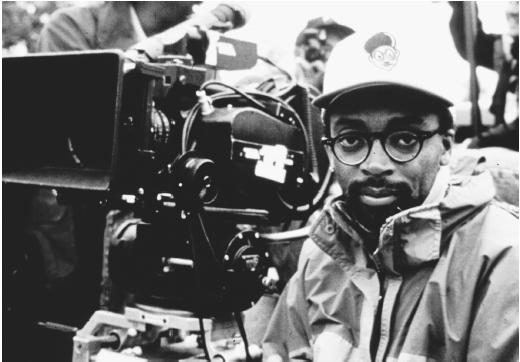

Spike Lee - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Shelton Jackson Lee in Atlanta, Georgia, 20 March 1957; son of jazz musician Bill Lee. Education: Morehouse College, B.A., 1979; New York University, M.A. in Filmmaking; studying with Martin Scorsese. Family: Married lawyer Tonya Linette Lewis, 1993; one son, Satchel. Career: Set up production company 40 Acres and a Mule; directed first feature, She's Gotta Have It , 1986; also directs music videos and commercials for Nike/Air Jordan; Trustee of Morehouse College, 1992. Awards: Student Directors Academy Award, for Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads , 1980; U.S. Independent Spirit Award for First Film, New Generation Award, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and Prix de Jeunesse, Cannes Film Festival, all for She's Gotta Have It , 1986; U.S. Independent Spirit Award, Best Picture, L.A. Film Critics, and Best Picture, Chicago Film Festival, all for Do the Right Thing , 1989; Essence Award, 1994. Address: 40 Acres and a Mule, 124 Dekalb Avenue, Suite 2, Brooklyn, NY 11217–1201, U.S.A.

Films as Director, Scriptwriter, and Editor:

- 1977

-

Last Hustle in Brooklyn (Super-8 short)

- 1980

-

The Answer (short)

- 1981

-

Sarah (short)

- 1982

-

Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (+ role, pr)

- 1986

-

She's Gotta Have It (+ role as Mars Blackmon, pr)

- 1988

-

School Daze (+ role as Half Pint, pr)

- 1989

-

Do the Right Thing (+ role as Mookie, pr)

- 1990

-

Mo' Better Blues (+ role as Giant)

- 1991

-

Jungle Fever (+ role as Cyrus, pr)

- 1992

-

Malcolm X (+ role as Shorty, pr)

- 1994

-

Crooklyn (+ role as Snuffy, pr)

- 1995

-

Clockers (+ role as Chucky)

- 1996

-

Girl 6 (+ role as Jimmy, pr); Get on the Bus (+ exec pr)

- 1997

-

4 Little Girls

- 1998

-

He Got Game (+ pr); Freak

- 1999

-

Summer of Sam (+ role as John Jeffries, pr)

- 2000

-

The Original Kings of Comedy ; Bamboozled

Other Films:

- 1993

-

The Last Party ( Youth for Truth ) (doc) (appearance); Seven Songs for Malcolm X (doc) (appearance); Hoop Dreams (doc) (appearance)

- 1994

-

DROP Squad (exec pr, appearance)

- 1995

-

New Jersey Drive (exec pr); Tales from the Hood (exec pr)

- 1999

-

The Best Man (pr)

- 2000

-

Famous (Dunne) (role as himself); Michael Jordan to the Max (Kempf and Stern) (role as himself); Love & Basketball (Gina Prince) (pr)

- 2001

-

3 A.M. (Lee Davis) (pr)

Publications

By LEE: books—

Spike Lee's She's Gotta Have It: Inside Guerilla Filmmaking , New York, 1987.

Uplift the Race: The Construction of School Daze , New York, 1988.

Do the Right Thing: A Spike Lee Joint , with Lisa Jones, New York, 1989.

Mo' Better Blues , with Lisa Jones, New York, 1990.

Five for Five: The Films of Spike Lee , New York, 1991.

By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X , with Ralph Wiley, New York, 1993.

Best Seat in the House: A Basketball Memoir , with Ralph Wiley, New York, 1997.

By LEE: articles—

Interview in New York Times , 10 August 1986.

Interview in Village Voice (New York), 12 August 1986.

"Class Act," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), January/February 1988.

"Entretien avec Spike Lee," in Cahiers du Cinéma , June 1989.

"Bed-Stuy BBQ," an interview with M. Glicksman, in Film Comment , July/August 1989.

"I Am Not an Anti-Semite," in New York Times , 22 August 1990.

Interview with Mike Wilmington, in Empire (London), October 1990.

"Entretien avec Spike Lee," with A. de Baecque and N. Saada, in Cahiers du Cinéma , June 1991.

Interview with M. Cieutat and Michael Ciment in Positif , July/August 1991.

"The Rolling Stone Interview: Spike Lee," with David Breskin, in Rolling Stone , July 1991.

"Spike Speaks," an interview with Lisa Kennedy, in Village Voice , 11 June 1991.

"Playboy Interview: Spike Lee," with Elvis Mitchell, in Playboy , July 1991.

"He's Gotta Have It," an interview with Janice M. Richolson, in Cineaste , no. 4, 1991.

"Generation X," an interview with H. L. Gates, Jr., in Black Film Review , no. 3, 1992.

"Just Whose Malcolm Is It, Anyway?" interview in New York Times , 31 May 1992.

"United Colors of Benetton," in Rolling Stone , 12 November 1992.

"Words with Spike Lee," an interview with J. C. Simpson, in Time , 23 November 1992.

Interview with David Breskin, in Inner Views: Filmmakers in Conversation , Boston, 1992.

"Entretien avec Spike Lee," with B. Bollag, in Positif , February 1993.

"Doing the Job," an interview with J. Verniere, in Sight and Sound , February 1993.

"Our Film Is Only a Starting Point," an interview with George Crowdus and Dan Georgakas, in Cineaste , no. 4, 1993.

"De qui parler?" an interview with V. Amiel and Jean-Pierre Coursodon, in Positif , February 1993.

"Is Malcolm X the Right Thing?" an interview with Lisa Kennedy, in Sight and Sound , February 1993.

"The Lees on Life," an interview with Lynn Darling, in Harper's Bazarr , May 1994.

"Spike Lee: The Do-the-Right-Thing Revolution," an interview with Henry Louis Gates, in Interview , October 1994.

"Spike on Sports," an interview with Daryl Howerton, in Sport , February 1995.

"Ghetto Master/Price Wars," an interview with Tom Charity and Brian Case, in Time Out (London), 31 January 1996.

Interview with N.O. Saeveras, in Film & Kino (Oslo), no. 1, 1996.

"The Sweet Hell of Success," an interview with P. Biskind, in Premiere (Boulder), October 1997.

On LEE: books—

Spike Lee and Commentaries on His Work , Bloomington, Indiana, 1992.

Patterson, Alex, Spike Lee , New York, 1992.

Bernotas, Bob, Spike Lee: Filmmaker , Hillside, New Jersey, 1993.

Lee, David, Malcolm X, Denzel Washington: A Spike Lee Joint , New York, 1992.

Chapman, Kathleen Ferguson, Spike Lee , Mankato, Minnesota, 1994.

Hardy, James Earl, Spike Lee , New York, 1996.

Jones, K. Maurice, Spike Lee and the African American Filmmakers: A Choice of Colors , Brookfield, Connecticut, 1996.

Haskins, Jim, Spike Lee: By Any Means Necessary, New York, 1997.

McDaniel, Melissa, Spike Lee: On His Own Terms, New York, 1998.

On LEE: articles—

Tate, G., "Spike Lee," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), September 1986.

Glicksman, M., "Lee Way," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1986.

Taylor, C., "The Paradox of Black Independent Cinema," in Black Film Review , no. 4, 1988.

Crouch, Stanley, " Do the Right Thing ," in Village Voice , 20 June 1989.

Davis, Thuliani, "We've Gotta Have It," in Village Voice , 20 June 1989.

Davis, T., "Local Hero," in American Film , July/August, 1989.

Sharkey, B., and T. Davis, "Knocking on Hollywood's Door," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), July/August 1989.

McDowell, J., "Profile: He's Got to Have It His Way," in Time , 17 July 1989.

Orenstein, Peggy, "Spike's Riot," in Mother Jones , September 1989.

Norment, L., "Spike Lee: The Man behind the Movies and the Controversy," in Ebony , October 1989.

Kirn, Walter, "Spike It Already," in Gentlemens Quarterly , August 1990.

George, N., "Forty Acres and an Empire," in Village Voice , 7 August 1990.

Hentoff, Nat, "The Bigotry of Spike Lee," in Village Voice , 4 September 1990.

O'Pray, Michael, "Do Better Blues—Spike Lee," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), October 1990.

Perkins, E., "Renewing the African American Cinema: The Films of Spike Lee," in Cineaste , no. 4, 1990.

Baecque, A. de, "Spike Lee," in Cahiers du Cinéma , May 1991.

Boyd, T., "The Meaning of the Blues," in Wide Angle , no. 3/4, 1991.

Breskin, D., "Spike Lee" in Rolling Stone , 11–25 July 1991.

Bates, Karen Grigsby, "They've Gotta Have Us," in New York Times Magazine , 14 July 1991.

Gilroy, Paul, "Spiking the Argument," in Sight and Sound , November 1991.

Grenier, Richard, "Spike Lee Fever," in Commentary , August 1991.

Hamill, Pete, "Spike Lee Takes No Prisoners," in Esquire , August 1991.

Backer, Houston A. Jr., "Spike Lee and the Commerce of Culture," in Black American Literature Forum , Summer 1991.

Whitaker, Charles, "Doing the Spike Thing," in Ebony , November 1991.

Johnson, A., "Moods Indigo: A Long View, Part 2," in Film Quarterly , Spring 1991.

Klein, Joe, "Spiked Again," in New York , 1 June 1992.

Elise, Sharon, "Spike Lee Constructs the New Black Man: Mo' Better," in Western Journal of Black Studies , Summer 1992.

Weinraub, B., "Spike Lee's Request: Black Interviewers Only," in New York Times , 29 October 1992.

Harrison, Barbara G., "Spike Lee Hates Your Cracker Ass," in Esquire , October 1992.

Wiley, R., "Great 'X'pectations," in Premiere , November 1992.

Reden, L., "Spike's Gang," in New York Times , 7 February 1993.

Hooks, Bill, "Male Heroes and Female Sex Objects: Sexism in Spike Lee's Malcolm X ," in Cineaste , no. 4, 1993.

Johnson, Victoria E., "Polyphone and Cultural Expression: Interpreting Musical Traditions in Do the Right Thing ," in Film Quarterly , Winter 1993.

Horne, Gerald, "Myth and the Making of Malcolm X ," in American Historical Review , April 1993.

Hirschberg, Lynn, "Living Large," in Vanity Fair , September 1993.

Pinsker, Sanford, "Spike Lee: Protest, Literary Tradition, and the Individual Filmmaker," in Midwest Quarterly , Autumn 1993.

Norment, Lynn, "A Revealing Look at Spike Lee's Changing Life," in Ebony , May 1994.

Rowland, Robert C., "Social Function, Polysemy, and Narrative-Dramatic Form: A Case Study of Do the Right Thing ," in Communication Quarterly , Summer 1994.

Hooks, Bell, "Sorrowful Black Death Is Not a Hot Ticket," in Sight and Sound , August 1994.

Lee, Jonathan Scott, "Spike Lee's Malcolm X as Transformational Object," in American Imago , Summer 1995.

Croal, M., "Bouncing off the Rim," in Newsweek , 22 April 1996.

Lightning, Robert K., and others, " Do the Right Thing: Generic Bases," in CineAction (Toronto), May 1996.

Jones, K., "Spike Lee," in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1997.

Pearson, H., "Get on the (Back of the) Bus," in Village Voice (New York), 7 January 1997.

Jones, Kent, "The Invisible Man: Spike Lee," in Film Comment (New York), January-February 1997.

MacDonald, Scott, "The City as the Country: The New York City Symphony from Rudy Burckhardt to Spike Lee," in Literature/ Film Quarterly (Salisbury), Winter 1997–1998.

McCarthy, Todd, " Summer of Sam ," in Variety (New York), 24 May 1999.

* * *

Spike Lee is the most famous African American to have succeeded in breaking through industry obstacles to create a notable career for himself as a major director. What makes this all the more notable is that he is not a comedian—the one role in which Hollywood has usually allowed blacks to excel—but a prodigious, creative, multifaceted talent who writes, directs, edits, and acts, a filmmaker who invites comparisons with American titans like Woody Allen, John Cassavetes, and Orson Welles.

His films, which deal with different facets of the black experience, are innovative and controversial even within the black community. Spike Lee refuses to be content with presenting blacks in their "acceptable" stereotypes: noble Poitiers demonstrating simple moral righteousness are nowhere to be found. Lee's characters are three-dimensional and often vulnerable to moral criticism. His first feature film, She's Gotta Have It , dealt with black sexuality, unapologetically supporting the heroine's promiscuity. His second film, School Daze , drawing heavily upon Lee's own experiences at Morehouse College, examined the black university experience and dealt with discrimination within the black community based on relative skin colors. His third film, Do the Right Thing , dealt with urban racial tensions and violence. His fourth film, Mo' Better Blues , dealt with black jazz and its milieu. His fifth film, Jungle Fever , dealt with interracial sexual relationships and their political implications, by no means taking the traditional, white liberal position that love should be color blind. His sixth film, Malcolm X , attempted no less than a panoramic portrait of the entire racial struggle in the United States, as seen through the life story of the controversial activist. Not until his seventh film, Crooklyn , primarily an autobiographical family remembrance of growing up in Brooklyn, did Spike Lee take a breath to deal with a simpler subject and theme.

Lee's breakthrough feature was She's Gotta Have It , an independent film budgeted at $175,000 and a striking box-office success: a film made by blacks for blacks which also attracted white audiences. She's Gotta Have It reflects the sensibilities of an already sophisticated filmmaker and harkens back to the early French New Wave in its exuberant embracing of bravura technique—intertitles, black-and-white cinematography, a sense of improvisation, characters directly addressing the camera—all wedded nevertheless to serious philosophical/sociological examination. The considerable comedy in She's Gotta Have It caused many critics to call Spike Lee the "black Woody Allen," a label which would increasingly reveal itself as a rather simplistic, muddle-headed approbation, particularly as Lee's career developed. (Indeed, in his work's energy, style, eclecticism, and social commitment, he more resembles Martin Scorsese, a Lee mentor at the NYU film school.) Even to categorize Spike Lee as a black filmmaker is to denigrate his talent, since there are today virtually no American filmmakers (except Allen) with the ambitiousness and talent to write, direct, and perform in their own films. And Lee edits as well.

Do the Right Thing , Lee's third full-length feature, is one of the director's most daring and controversial achievements, presenting one sweltering day which culminates in a riot in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. From its first images—assailing jump cuts of a woman dancing frenetically to the rap "Fight the Power" while colored lights stylistically flash on a location ghetto block upon which Lee has constructed his set—we know we are about to witness something deeply disturbing. The film's sound design is incredibly dense and complex, and the volume alarmingly high, as the film continues to assail us with tight close-ups, extreme angles, moving camera, colored lights, distorting lenses, and individual scenes directed like high operatic arias.

Impressive, too, is the well-constructed screenplay, particularly the perceptively drawn Italian family at the center of the film who feel so besieged by the changing, predominantly black neighborhood around them. A variety of ethnic characters are drawn sympathetically, if unsentimentally; perhaps never in American cinema has a director so accurately presented the relationships among the American urban underclasses. Particularly shocking and honest is a scene in which catalogs of racial and ethnic epithets are shouted directly into the camera. The key scene in Do the Right Thing has the character of Mookie, played by Spike Lee, throwing a garbage can through a pizzeria window as a moral gesture which works to make the riot inevitable. The film ends with two quotations: one from Martin Luther King Jr., eschewing violence; the other from Malcolm X, rationalizing violence in certain circumstances.

Do the Right Thing was one of the most controversial films of the last twenty years. Politically conservative commentators denounced the film, fearful it would incite inner-city violence. Despite widespread acclaim the film was snubbed at the Cannes Film Festival, outraging certain Cannes judges; despite the accolades of many critics' groups, the film was also largely snubbed by the Motion Picture Academy, receiving a nomination only for Spike Lee's screenplay and Danny Aiello's performance as the pizzeria owner.

Both Mo' Better Blues and the much underrated Crooklyn owe a lot to Spike Lee's appreciation of music, particularly as handed down to him by his father, the musician Bill Lee. Crooklyn is by far the gentler film, presenting Lee and his siblings' memories of growing up with Bill Lee and his mother. Typical of Spike Lee, the vision in Crooklyn is by no means a sentimental one, and the father comes across as a proud, if weak, man; talented, if failing in his musical career; loving his children, if not always strong enough to do the right thing for them. The mother, played masterfully by Alfre Woodard, is the stronger of the two personalities; and the film—ending as it does with grief—seems Spike Lee's version of Fellini's Amarcord. For a white audience, Crooklyn came as a revelation: the sight of black children watching cartoons, eating Trix cereal, playing hopscotch, and singing along with the Partridge family, seemed strange—because the American cinema had so rarely (if ever?) shown a struggling black family so rooted in the popular-culture iconography to which all Americans could relate. Scene after scene is filled with humanity, such as the little girl stealing groceries rather than be embarrassed by using her mother's food stamps. Crooklyn 's soundtrack, like so many other Spike Lee films, is unusually cacophonous, with everyone talking at once, and its improvisational style suggests Cassavetes or Scorsese. Lee's 1995 film, Clockers , which deals with drug dealing, disadvantage, and the young "gangsta," was actually produced in conjunction with Scorsese, whose own work, particularly the seminal Meanstreets , Lee's work often recalls.

Another underrated film from Lee is Jungle Fever (1991). Taken for granted is how well the film communicates the African-American experience; more surprising is how persuasively and perceptively the film communicates the Italian-American experience, particularly working-class attitudes. Indeed, one looks in vain in the Hollywood cinema for an American director with a European background who presents blacks with as many insights as Lee presents his Italians. And certainly unforgettable, filmed expressively with nightmarish imagery, is the film's set-piece in which we enter a crack house and come to understand profoundly and horrifically the tremendous damage being done to a component of the African-American community by this plague. Jungle Fever , like Do the Right Thing , basically culminates in images of Ruby Dee screaming in horror and pain, a metaphor for black martyrdom and suffering.

Nevertheless, the most important film in the Spike Lee oeuvre (if not his best) is probably Malcolm X —important because Lee himself campaigned for the film when it seemed it would be given to a white director, creating then an epic with the sweep and majesty of a David Lean and a clear political message of black empowerment. If the film on the whole seems less interesting than many of Lee's films (because there is less Lee there), the most typical Lee touches (such as the triumphant coda which enlists South African President Nelson Mandela to play himself and teach young blacks about racism and their future) seem among the film's most inspired and creative scenes. If more cautious and conservative, in some ways the film is also Lee's most ambitious: with dozens of characters, historical reconstructions, and the biggest budget in his entire career. Malcolm X proved definitively to fiscally conservative Hollywood studio executives that an African-American director could be trusted to direct a high-budget "A film." The success of Malcolm X , coupled with the publicity machine supporting Spike Lee, helped a variety of young black directors—like John Singleton, the Wayans brothers, and Mario Van Peebles—all break through into mainstream Hollywood features.

And indeed, Lee seems often to be virtually everywhere. On television interview shows he is called upon to comment on every issue relevant to black America: from the O. J. Simpson verdict to Louis Farrakhan and the Million Man March. In bookstores, his name can be found on a variety of published books on the making of his films, books created by his own public relations arm particularly so that others can read about the process, become empowered, find their own voices, and follow in Lee's filmic footsteps. On the basketball court, Lee can be found very publicly attending the New York Knicks' games. On MTV, he can be found in notable commercials for Nike basketball shoes. On college campuses, he can be found making highly publicized speeches on the issues of the day. And on the street, his influence can be seen even in fashion trends—such as the ubiquitous "X" on a variety of clothing the year of Malcolm X 's release. There may be no other American filmmaker working today who is so willing to take on all comers, so politically committed to make films which are consistently and unapologetically in-your-face. Striking, too, is that instead of taking his inspiration from other movies, as do the gaggle of Spielberg imitators, Lee takes his inspiration from real life—whether the Howard Beach or Yusuf Hawkins incidents, in which white racists killed blacks, or his own autobiographical memories of growing up black in Brooklyn.

As Spike Lee has become a leading commentator on the cultural scene, there has been an explosion of Lee scholarship, not all of it laudatory: increasing voices attack Lee and his films for either homophobia, sexism, or anti-Semitism. Lee defends both his films and himself, pointing out that because characters espouse some of these values does not imply that he himself does, only that realistic portrayal of the world as it is has no place for political correctness. Still, some of the accusers point to examples which give pause: Lee's insistence on talking only to black journalists for stories about Malcolm X , but refusing to meet with a black journalist who was gay; the totally cartoonish portrait of the homosexual neighbor in Crooklyn , one of the few characters in that film who is given no positive traits to leaven the harsh criticism implied by Lee's treatment or to make him seem three-dimensional. Similar points have been made regarding Lee's attitudes toward Jews (particularly in Mo' Better Blues ) and women. At one point, Lee even felt the need to defend himself in the New York Times in a letter to the editor titled, "Why I Am Not an Anti-Semite."

If Malcolm X brought Lee more attention than ever before, the films he has made since brought critical and/or financial disappointment. Clockers starts powerfully enough with a close-up of a bullet hole and a montage of horrifically graphic images of violence victims. Although Clockers realistically evokes the world of adolescent cocaine dealers within the limited world of a Brooklyn housing project, Clockers ultimately reveals Lee to be either not particularly skillful at or not particularly interested in telling a traditional story. Girl 6 and Get on the Bus reveal similar attitudes toward dramatic narrative. A visually pyrotechnical examination of a fetching contradiction, Girl 6 presents a young black woman circumspect in her private life who nevertheless works as a phone-sex operator. Although not written by Spike Lee, this experimental work's flaccid narrative is pumped up by its stunning cinematography. The weirdest scene undoubtedly is a postmodern parody of the television show The Jeffersons ; in certain regards Lee's multiple diegeses in Girl 6 suggest an imitation of Oliver Stone's controversial Natural Born Killers. Although startlingly inventive in the manner of Jean-Luc Godard, Girl 6 was destined, despite its florid subject, to frustrate a popular audience searching for simple coherence.

Get on the Bus , like many of Lee's films, takes a real historical event as its inspiration: the Million Man March organized by Louis Farrakhan. A beautifully evocative credit sequence of a black man in chains cuts to a cross on a church in South Central Los Angeles—certainly an ambiguous juxtaposition. In Get on the Bus , a variety of black men—each representative of a different strain of the black experience—must share a long, cross-country bus ride on their way to the Washington, D.C. march, a conception which recalls the classic American film à thèse of the fifties (for instance, the Sidney Lumet/Reginald Rose Twelve Angry Men ), where each metaphorical character is respectively given the spotlight, often through a moving monologue or dramatic scene, thus allowing the narrative to accrue a variety of psychological/sociological insights. Notably for the Lee oeuvre, Get on the Bus includes black gay lovers who are treated three-dimensionally (tellingly, only the black Republican is treated with total derision, thrown off the bus in a scene of comic relief). Like much of Lee's work, this film has a continuous impulse for music. And there is one stunning montage of beautiful ebony faces. Nevertheless, the ending of the film seems anti-climactic, because the characters never quite make it to the Million Man March—a disappointing narrative choice perhaps dictated by Lee's low budget.

He Got Game , like many Lee films, seems meandering and a bit undisciplined, if with important themes: here, of father/son reconciliation, and the meaning of basketball within black culture. Indeed, never have basketball images been photographed so expressively; and apposite, parallel scenes of one-on-one father/son competition highlight the film. Like Accatone , where Pasolini used Bach on his soundtrack to ennoble his lower-class youth, Lee brilliantly uses the most American composer of all, the lyrical Aaron Copland. Summer of Sam likewise has some extraordinary elements, particularly Lee's perceptive anatomizing of the complicated sex lives of his Italian and African-American characters. Rarely, too, has a film so expressively evoked such a precise sense of place and time—that chaotic summer when New York City was obsessed and terrified by the Son of Sam serial killer. Unfortunately, audiences were largely indifferent to Lee's interest in character and texture, disappointed that Summer of Sam did not offer a more traditional narrative focused on the killer and his sadism, in the typical Hollywood style.

Curiously, one notes that Lee's documentary for HBO, 4 Little Girls , reveals some of the same problems as Lee's recent fiction career. A documentary on a powerfully compelling subject—the four little girls killed in a church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963— 4 Little Girls , though politically fascinating, is curiously slack, with its narrative as its weakest link, Lee failing to clearly differentiate his characters and not building suspensefully to a clear climax. Stronger are the film's individual parts: such as the killer's attorney characterizing Birmingham as "a wonderful place to live and raise a family," while Lee shows us an image of a little child in full Klan regalia, hand-in-hand with a parent; or one parent's the memory of Martin Luther King Jr.'s memorable oration at the funeral—"Life is as hard as steel!"

As Lee's career progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that his interest in political insight and the veracity of historical details is what impedes his ability to tell a story in the way the popular audience expects. Whereas Lee once seemed the most likely minority filmmaker to transform the Hollywood establishment, he now seems the filmmaker (like, perhaps Woody Allen) most perpetually in danger of losing his core audience. Do the Right Thing and Malcolm X were successful precisely because Lee was able to fuse popular forms and audience-pleasing entertainment with significant cultural commentary. Lee seems now to be making films which—despite their ambitious subjects and sophisticated points-of-view—disappear almost entirely off the cultural radar screen.

Interesting, almost as an aside, is Lee's canny ability, particularly in his earlier films, to use certain catch phrases which helped both to attract and delight audiences. In She's Gotta Have It , there was the constant refrain uttered by Spike Lee as Mars Blackmon, "Please baby, please baby, please baby, baby, baby, please. . . "; in Do the Right Thing , the disc jockey's "And that's the truth, Ruth." Notable also is the director's assembly—in the style of Bergman and Chabrol and Woody Allen in their prime—of a consistent stable of very talented collaborators, including his father, Bill Lee, as musical composer, production designer Wynn Thomas, producer Monty Ross, and cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, among others. Lee has also used many of the same actors from one film to another, including his sister Joie Lee, Wesley Snipes, Denzel Washington, John Turturro, Samuel L. Jackson, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee, helping to create a climate which propelled several to stardom and inspired a new wave of high-level attention to a variety of breakout African-American performers.

—Charles Derry

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: