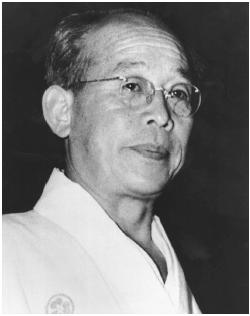

Kenji Mizoguchi - Director

Nationality:

Japanese.

Born:

Tokyo, 16 May 1898.

Education:

Aohashi Western Painting Research Institute, Tokyo, enrolled 1914.

Career:

Apprentice to textile designer, 1913; newspaper illustrator, Kobe, 1916;

assistant director to Osamu Wakayama, 1922; directed first film, 1923;

began association with art director Hiroshi Mizutani on

Gio matsuri

, 1933; began collaboration with writer Yoshikata Yoda on

Naniwa ereji

, 1936; member of Cabinet Film Committee, from 1940; elected president of

Japanese directors association, 1949; signed to Daiei Company, 1952.

Awards:

International Prize, Venice Festival, for

The Life of Oharu

, 1952.

Died:

24 August 1956, in Kyoto, Japan, of leukemia.

Films as Director:

- 1923

-

Ai ni yomigaeru hi ( The Resurrection of Love ); Furusato ( Hometown ) (+ sc); Seishun no yumeji ( The Dream Path of Youth ) (+ sc); Joen no chimata ( City of Desire ) (+ sc); Haizan no uta wa kanashi ( Failure's Song Is Sad ) (+ sc); 813 ( 813: The Adventures of Arsene Lupin ); Kiri no minato ( Foggy Harbor ); Chi to rei ( Blood and Soul ) (+ sc); Yoru ( The Night ) (+ sc); Haikyo no naka ( In the Ruins )

- 1924

-

Toge no uta ( The Song of the Mountain Pass ) (+ sc); Kanashiki hakuchi ( The Sad Idiot ) (+ story); Gendai no joo ( The Queen of Modern Times ); Josei wa tsuyoshi ( Women Are Strong ); Jinkyo ( This Dusty World ); Shichimencho no yukue ( Turkeys in a Row ); Samidare zoshi ( A Chronicle of May Rain ); Musen fusen ( No Money, No Fight ); Kanraku no onna ( A Woman of Pleasure ) (+ story); Akatsuki no shi ( Death at Dawn )

- 1925

-

Kyohubadan no joo ( Queen of the Circus ); Gakuso o idete ( Out of College ) (+ sc); Shirayuri wa nageku ( The White Lily Laments ); Daichi wa hohoemu ( The Earth Smiles ); Akai yuhi ni terasarete ( Shining in the Red Sunset ); Furusato no uta ( The Song of Home ); Ningen ( The Human Being ); Gaijo no suketchi ( Street Sketches )

- 1926

-

Nogi Taisho to Kuma-san ( General Nogi and Kuma-san ); Doka o ( The Copper Coin King ) (+ story); Kaminingyo haru no sayaki ( A Paper Doll's Whisper of Spring ); Shin ono ga tsumi ( My Fault, New Version ); Kyoren no onna shisho ( The Passion of a Woman Teacher ); Kaikoku danji ( The Boy of the Sea ); Kane ( Money ) (+ story)

- 1927

-

Ko-on ( The Imperial Grace ); Jihi shincho ( The Cuckoo )

- 1928

-

Hito no issho ( A Man's Life )

- 1929

-

Nihombashi (+ sc); Tokyo koshinkyoku ( Tokyo March ); Asahi wa kagayaku ( The Morning Sun Shines ); Tokai kokyogaku ( Metropolitan Symphony )

- 1930

-

Furusato ( Home Town ); Tojin okichi ( Mistress of a Foreigner )

- 1931

-

Shikamo karera wa yuku ( And Yet They Go )

- 1932

-

Toki no ujigami ( The Man of the Moment ); Mammo Kenkoku no Reimei ( The Dawn of Manchukuo and Mongolia )

- 1933

-

Taki no Shiraito ( Taki no Shiraito, the Water Magician ); Gion matsuri ( Gion Festival ) (+ sc); Jimpuren ( The Jimpu Group )(+ sc)

- 1934

-

Aizo toge ( The Mountain Pass of Love and Hate ); Orizuru osen ( The Downfall of Osen )

- 1935

-

Maria no Oyuki ( Oyuki the Madonna ); Gubijinso ( Poppy )

- 1936

-

Naniwa ereji ( Osaka Elegy ) (+ story); Gion no shimai ( Sisters of the Gion ) (+ story)

- 1937

-

Aienkyo ( The Straits of Love and Hate )

- 1938

-

Aa furusato ( Ah, My Home Town ); Roei no uta ( The Song of the Camp )

- 1939

-

Zangiku monogatari ( The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum )

- 1944

-

Danjuro sandai ( Three Generations of Danjuro ); Miyamoto Musashi ( Musashi Miyamoto )

- 1945

-

Meito Bijomaru ( The Famous Sword Bijomaru ); Hisshoka ( Victory Song ) (co-d)

- 1946

-

Josei no shori ( The Victory of Women ); Utamaro o meguru gonin no onna ( Utamaro and His Five Women )

- 1947

-

Joyu Sumako no koi ( The Love of Sumako the Actress )

- 1948

-

Yoru no onnatachi ( Women of the Night )

- 1949

-

Waga koi wa moenu ( My Love Burns )

- 1950

-

Yuki Fujin ezu ( A Picture of Madame Yuki )

- 1951

-

Oyu-sama ( Miss Oyu ); Musashino Fujin ( Lady Musashino )

- 1952

-

Saikaku ichidai onna ( The Life of Oharu )

- 1953

-

Ugetsu monogatari ( Ugetsu ); Gion bayashi ( Gion Festival Music )

- 1954

-

Sansho dayu ( Sansho the Bailiff ); Uwasa no onna ( The Woman of the Rumor ); Chikamatsu monogatari ( A Story from Chikamatsu ; Crucified Lovers )

- 1955

-

Yokihi ( The Princess Yang Kwei-fei ); Shin Heike monogatari ( New Tales of the Taira Clan )

- 1956

-

Akasen chitai ( Street of Shame )

- 1957

-

Osaka monogatari ( An Osaka Story )

Publications

By MIZOGUCHI: articles—

Texts, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1959.

"Kenji Mizoguchi," in Positif (Paris), November 1980.

"Table ronde avec Kenji Mizoguchi" in Positif (Paris), December 1980 and January 1981.

On MIZOGUCHI: books—

Anderson, Joseph, and Donald Richie, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry , New York, 1960.

Ve-Ho, Kenji Mizoguchi , Paris, 1963.

Mesnil, Michel, Mizoguchi Kenji , Paris, 1965.

Iwazaki, Akira, "Mizoguchi," in Anthologie du Cinéma , vol. 3, Paris, 1968.

Yoda, Yoshikata, Mizoguchi Kenji no hito to geijutsu [Kenji Mizoguchi: The Man and His Art], Tokyo, 1970.

Mesnil, Michel, editor, Kenji Mizoguchi , Paris, 1971.

Mellen, Joan, Voices from the Japanese Cinema , New York, 1975.

Mellen, Joan, The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan Through Its Cinema , New York, 1976.

Bock, Audie, Japanese Film Directors , New York, 1978; revised edition, Tokyo, 1985.

Freiberg, Freda, Women in Mizoguchi Films , Melbourne, 1981.

Serceau, Daniel, Mizoguchi: De la revolte aux songes , Paris, 1983.

Andrew, Dudley, Film in the Aura of Art , Princeton, New Jersey, 1984.

McDonald, Keiko, Mizoguchi , Boston, 1984.

Kirihara, Donald, Patterns of Time: Mizoguchi and the 1930s , Madison, 1992.

On MIZOGUCHI: articles—

Mizoguchi issue of Cinéma (Paris), no. 6, 1955.

Anderson, Joseph, and Donald Richie, "Kenji Mizoguchi," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1955.

Rivette, Jacques, "Mizoguchi vu d'ici," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 81, 1958.

Godard, Jean-Luc, "L'Art de Kenji Mizoguchi," in Art (Paris), no. 656, 1958.

Mizoguchi issue of L'Ecran (Paris), February/March 1958.

Mizoguchi issue of Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1958.

"Dossier Mizoguchi," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), August/September 1964.

"The Density of Mizoguchi's Scripts," in interview with Yoshikata Yoda, in Cinema (Los Angeles), Spring 1971.

Wood, Robin, "Mizoguchi: The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Catcher," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1973.

"Les Contes de la lune vague après la pluie," special Mizoguchi issue of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 1 January 1977.

Cohen, R., "Mizoguchi and Modernism," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1978.

Legrand, G., and others, special Mizoguchi section, in Positif (Paris), November 1978.

Sato, Tadao, and Dudley Andrew, "On Kenji Mizoguchi," in Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Spring 1980.

Andrew, Dudley, "Kenji Mizoguchi: La Passion de la identification," in Positif (Paris), January 1981.

Leach, J., "Mizoguchi and Ideology," in Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Fall 1983.

Douchet, J. and others, "Traverses Mizoguchi," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1993.

Le Fanu, Mark, "Autour de Mizoguchi," in Positif (Paris), June 1993.

Nemes, K., "Mizogucsi Kendzsi," in Filmkultura (Budapest), October-December 1993.

Janakiev, Aleksander, "Elitarna projava," in Kino (Sophia), no. 6, 1993–1994.

Kirihara, Donald, in East-West (Honolulu), January 1994.

Roger, Philippe, "Mizoguchi inédit," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), no. 228, Summer 1994.

Burdeau, Emanuel and others, "Mizoguchi Encore," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July-August 1996.

Brown, G., "Casting Spells," in Village Voice (New York), 24 September 1996.

Macnab, Geoffrey, in Sight and Sound (London), December 1998.

* * *

By any standard Kenji Mizoguchi must be considered among the world's greatest directors. Known in the West for the final half-dozen films which crowned his career, Mizoguchi considered himself a popular as well as a serious artist. He made eighty-five films during his career, evidence of that popularity. Like John Ford, Mizoguchi is one of the few directorial geniuses to play a key role in a major film industry. In fact, Mizoguchi once headed the vast union governing all production personnel in Japan, and was awarded more than once the industry's most coveted citations. But it is as a meticulous, passionate artist that Mizoguchi will be remembered. His temperament drove him to astounding lengths of research, rehearsal, and execution. Decade after decade he refined his approach while energizing the industry with both his consistency and his innovations.

Mizoguchi's obsessive concern with ill-treated women, and his maniacal pursuit of a lofty notion of art, stemmed from his upbringing. His obstinate father, unsuccessful in business, refused to send his older son beyond primary school. With the help of his sister, a onetime geisha who had become the mistress of a wealthy nobleman, Mizoguchi managed to enroll in a Western-style art school. For a short time he did layout work and wrote reviews for a newspaper, but his real education came through the countless books he read and the theater he attended almost daily. In 1920 he presented himself as an actor at Nikkatsu studio, where a number of his friends worked. He moved quickly into scriptwriting, then became an assistant director, and finally a director. Between 1922 and 1935, he made fifty-five films, mostly melodramas, detective stories, and adaptations. Only six of these are known to exist today.

Though these lost films might show the influences his work had on the development of other Japanese films, German expressionism, and American dramatic filmmaking (not to mention Japanese theatrical style and western painting and fiction), Mizoguchi himself dismissed his early efforts, claiming that his first real achievement as an artist came in 1936. Working for the first time with scriptwriter Yoshikata Yoda, who would be his collaborator on nearly all his subsequent films, he produced Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion , stories of exploited women in contemporary Japan. Funded by Daiichi, a tiny independent company he helped set up to bypass big-studio strictures, these films were poorly distributed and had trouble with the censors on account of their dark realism and touchy subject. While these films effectively bankrupted Daiichi, they also caused a sensation among the critics and further secured Mizoguchi's reputation as a powerful, if renegade, force in the industry.

Acknowledged by the wartime culture as Japan's chief director, Mizoguchi busied himself during the war mainly with historical dramas which were ostensibly non-political, and thus acceptable to the wartime government. Under the Allied occupation Mizoguchi was encouraged to make films about women, in both modern and historical settings, as part of America's effort to democratize Japanese society. With Yoda as scriptwriter and with actress Kinuyo Tanaka as star, the next years were busy but debilitating for Mizoguchi. He began to be considered old-fashioned in technique, even if his subjects were of a volatile nature.

Ironically, it was the West which resuscitated this most oriental director. With his critical and box-office reputation on the decline, Mizoguchi decided to invest everything in The Life of Oharu , a classic seventeenth-century Japanese picaresque story, and in 1951 he finally secured sufficient financing to produce it himself. Expensive, long, and complex, Oharu was not a particular success in Japan, but it gained an international reputation for Mizoguchi when it won the grand prize at Venice. Daiei Films, a young company that took Japanese films and aimed them at the export market, then gave Mizoguchi virtual carte blanche in his filmmaking. Under such conditions, he was able to create his final string of masterpieces, beginning with Ugetsu , his most famous film.

Mizoguchi's fanatic attention to detail, his insistence on multiple rewritings of Yoda's scripts, and his calculated tyranny over actors are legendary, as he sought perfection demanded by few other film artists. He saw his later films as the culmination of many years' work, his style evolving from one in which a set of tableaux were photo-graphed from an imperial distance and then cut together (one scene/one shot) to one in which the camera moves between two moments of balance, beginning with the movements of a character, then coming to rest at its own proper point.

It was this later style which hypnotized the French critics and through them the West in general. The most striking oppositions in his themes and dramas (innocence vs. guilt, good vs. bad) unroll like a seamless scroll until in the final camera flourish one feels the achievement of a majestic, stoic contemplation of life.

More recently Mizoguchi's early films have come under scrutiny, both for their radical stylistic innovations (such as the shared flashbacks of the 1935 Downfall of Osen ) and for the radical political positions which they virtually shriek (in the final close-ups of Sisters of the Gion and Osaka Elegy , for instance). When charges of mysticism are levelled at Mizoguchi, it is good to recall that his final film, Street of Shame , certainly helped bring about the ban on prostitution in Japan in 1957.

A profound influence on the New Wave directors, Mizoguchi continues to fascinate those in the forefront of the art (Godard, Straub, Rivette). Complete retrospectives of his thirty-one extant films in Venice, London, and New York resulted in voluminous publications about Mizoguchi in the 1980s. A passionate but contemplative artist, struggling with issues crucial to cinema and society, Mizoguchi will continue to reward anyone who looks closely at his films. His awesome talent, self-discipline, and productivity guarantee this.

—Dudley Andrew

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: