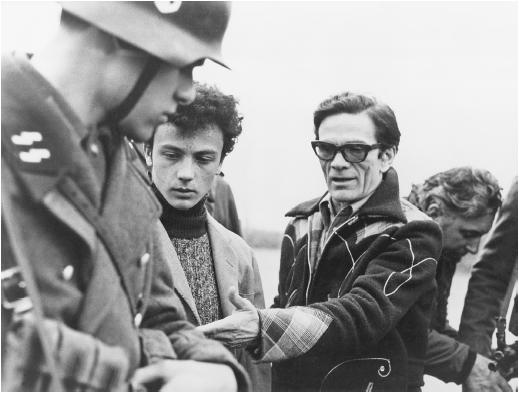

Pier Paolo Pasolini - Director

Nationality:

Italian.

Born:

Bologna, 5 March 1922.

Education:

School Reggio Emilia e Galvani, Bologna, until 1937; University of

Bologna, until 1943.

Military Service:

Conscripted, 1943; regiment taken prisoner by Germans following Italian

surrender; escaped and took refuge with family in Casarsa.

Career:

Formed "Academiuta di lenga furlana" with friends,

publishing works in Friulian dialect, 1944; secretary of Communist Party

cell in Casarsa, 1947; accused of corrupting minors, sacked from teaching

post, moved to Rome, 1949; teacher in Ciampino, suburb of Rome, early

1950s; following publication of

Ragazzi di vita

, indicted for obscenity, 1955; co-founder and editor of review

Officina

(Bologna); prosecuted for "vilification of the Church" for

directing "La ricotta" episode of

Rogopag

, 1963.

Awards:

Special Jury Prize, Venice Festival, for

Il vangelo secondo Matteo

, 1964.

Died:

Bludgeoned to death in Ostia, 2 November 1975; buried at Casarsa.

Films as Director:

- 1961

-

Accattone (+ sc)

- 1962

-

Mamma Roma (+ sc)

- 1963

-

"La ricotta" episode of Rogopag (+ sc); La rabbia (part one)(+ sc)

- 1964

-

Comizi d'amore (+ sc); Sopralluoghi in Palestina (+ sc); Il vangelo secondo Matteo ( The Gospel according to Saint Matthew ) (+ sc)

- 1966

-

Uccellacci e uccellini ( The Hawks and the Sparrows ) (+ sc);"La terra vista dalla luna" episode of Le Streghe ( The Witches ) (+ sc)

- 1967

-

"Che cosa sono le nuvole" episode of Cappriccio all'italiana (+ sc); Edipo re ( Oedipus Rex ) (+ sc)

- 1968

-

Teorema (+ sc); "La sequenza del fiore di carta" episode of Amore e rabbia (+ sc)

- 1969

-

Appunti per un film indiano (+ sc); Appunti per una Orestiade africana ( Notes for an African Oresteia ) (+ sc); Porcile ( Pigsty ; Pigpen ) (+ sc); Medea (+ sc)

- 1971

-

Il decameron ( The Decameron ) (+ sc, role as Giotto)

- 1972

-

12 dicembre (co-d, sc); I racconti di Canterbury ( The Canterbury Tales ) (+ sc, role)

- 1974

-

Il fiore delle mille e una notte ( A Thousand and One Nights )(+ sc)

- 1975

-

Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodome ( Salo—The 120 Days of Sodom ) (+ co-sc)

Other Films:

- 1954

-

La donna del fiume (co-sc)

- 1955

-

Il prigioniero della montagna (co-sc)

- 1956

-

Le notti di Cabiria (Fellini) (co-sc)

- 1957

-

Marisa la civetta (Bolognini) (co-sc)

- 1958

-

Giovanni Mariti (Bolognini) (co-sc)

- 1959

-

La notte brava (Bolognini) (co-sc)

- 1960

-

La canta delle marane (sc); Morte di un amico (co-sc); Il bell' Antonio (Bolognini) (co-sc); La giornata balorda (Bolognini)(co-sc); La lunga notte del '43 (co-sc); Il carro armato dell '8 settembre (co-sc); Il gobbo (role)

- 1961

-

La ragazza in vetrina (co-sc)

- 1962

-

La commare secca (Bertolucci) (sc)

- 1966

-

Requiescat (role)

- 1969

-

Ostia (co-sc)

- 1973

-

Storie scellerate (co-sc)

Publications

By PASOLINI: books—

Poesie e Casarsa , Bologna, 1942.

Dov'è la mia patria , Casarsa, 1949.

I parlanti , Rome, 1951.

Tal cour di un frut , Tricesimo, 1953.

Del "diario" (1945–47) , Caltanissetta, 1954.

Il canto popolare , Milan, 1954.

La meglio gioventù , Florence, 1954.

Ragazzi di vita , Milan, 1955; published as The Ragazzi , New York, 1968.

L'usignolo della Chiesa Cattolica , Milan, 1958.

Una vita violenta , Milan, 1959.

Donne di Roma , Milan, 1960.

Passione e ideologia (1948–1958), Milan, 1960.

Roma 1950, diario , Milan, 1960.

Sonetto primaverile (1953) , Milan, 1960.

Accattone , Rome, 1961.

Il sogno di una cosa , Milan, 1962.

La violenza , with drawings by Attardi and others, Rome, 1962; published as A Violent Life , New York, 1968.

L'odore dell'India , Milan, 1962.

Mamma Roma , Milan, 1962.

Il vantone di Plauto , Milan, 1963.

Il vangelo secondo Matteo , Milan, 1964.

Alì degli occhi azzurri , Milan, 1965.

Poesie dimenticate , Udine, 1965.

Uccellacci e uccellini , Milan, 1965.

Edipo re , Milan, 1967; published as Oedipus Rex , London, 1971.

Teorema , Milan, 1968.

Pasolini on Pasolini , interviews by Oswald Stack, London, 1969.

Medea , Milan, 1970.

Poesie , Milan, 1970.

Empirismo eretico , Milan, 1972.

Calderón , Milan, 1973.

Il padre selvaggio , Turin, 1975.

La divina Mimesis , Turin, 1975.

La nuova gioventù , Turin, 1975.

Scritti corsari , Milan, 1975.

Trilogia della vita , edited by Giorgio Gattei, Bologna, 1975.

I turcs tal Friùl , Udine, 1976.

L'arte del Romanino e il nostro tempo , Brescia, 1976.

Lettere agli amici (1941–1945) , Milan, 1976.

L'Experience hérétique: langue et cinéma , Paris, 1976.

"Volgar" eloquio , edited by A. Piromalli and D. Scarfoglio, Naples, 1976.

Affabulazione , Pilade, Milan, 1977.

Le belle bandiere: dialoghi 1960–65 , Rome, 1977.

San Paolo , Turin, 1977.

I disegni, 1941–1975 , Milan, 1978.

Poems , edited by Norman Macafee and Luciano Martinengo, New York, 1982.

Lettere, 1940–1954: Con una cronologia della vita e delle opere , edited by Nico Naldini, Turin, 1986.

Lettere, 1955–1975: Con una cronologia della vita e delle opere , edited by Nico Naldini, Turin, 1988.

By PASOLINI: articles—

"Intellectualism . . . and the Teds," in Films and Filming (London), January 1961.

"Cinematic and Literary Stylistic Figures," in Film Culture (New York), Spring 1962.

"Pier Paolo Pasolini: An Epical-Religious View of the World," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1965.

Interview with James Blue, in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1965.

"Pasolini—A Conversation in Rome," with John Bragin, in Film Culture (New York), Fall 1966.

Interview in Interviews with Film Directors , edited by Andrew Sarris, New York, 1967.

"Montage et sémiologie selon Pasolini," in Cinéma (Paris), March 1972.

"Pasolini Today," an interview with Gideon Bachmann, in Take One (Montreal), September 1974.

"The Scenario as a Structure Designed to Become Another Structure," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), vol. 2, no. 1, 1978.

"Toto," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1979.

Brang, H., S. Beltrami, and P.P. Pasolini, "Leidenschaft und Trauer. Pasolini als Filmkritiker. San Paolo," Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), special section, vol 16., March 1988.

Giavarini, L., and P.P. Pasolini, "Pasolini, la parole ininterrompue," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1992.

On PASOLINI: books—

Gervais, Marc, Pier Paolo Pasolini , Paris, 1973.

Taylor, John, Directors and Directions , New York, 1975.

Siciliano, Enzo, Vita di Pasolini , Milan, 1978.

Bertini, Antonio, Teoria e tecnica del film in Pasolini , Rome, 1979.

Snyder, Stephen, Pier Paolo Pasolini , Boston, 1980.

Bellezza, Dario, Morte di Pasolini , Milan, 1981.

Bergala, Alain, and Jean Narboni, editors, Pasolini cinéaste , Paris, 1981.

Gerard, Fabien S., Pasolini: ou, Le mythe de la barbarie , Brussels, 1981.

Boarini, Vittorio, and others, Da Accattone a Salo: 120 scritti sul cinema di Pier Paolo Pasolini , Bologna, 1982.

Siciliano, Enzo, Pasolini: A Biography , New York, 1982.

De Giusti, Luciano, I film di Pier Paolo Pasolini , Rome, 1983.

Carotenuto, Aldo, L'autunno della conscienza: Ricerche psicologiche su Pier Paolo Pasolini , Turin, 1985.

Michalczyk, John J., The Italian Political Filmmakers , Cranbury, New Jersey, 1986.

Schweitzer, Otto, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten , Hamburg, 1986.

Klimke, Cristoph, Kraft der Vergangenheit: Zu Motiven der Filme von Pier Paolo Pasolini , Frankfurt, 1988.

Greene, Naomi, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Cinema as Heresy , Princeton, New Jersey, 1990.

Schwartz, Barth David, Pasolini Requiem , New York, 1992.

Maurizio, Viano, A Certain Realism: Toward a Use of Pasolini's Film Theory and Practice , Berkeley, California, 1993.

Rumble, Patrick, and Bart Testa, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Contemporary Perspectives , Toronto, 1993.

Murri, Serafino, Pier Paolo Pasolini , Rome, 1994.

Peterson, Thomas E., The Paraphase of an Imaginary Dialogue: The Poetics and Poetry of Pier Pasolini , New York, 1994.

Moscati, Italo, Pasolini e il teorema del sesso: 1968, dalla Mostra del cinema al sequestro : un anno vissuto nello scandalo , Milan, 1995.

On PASOLINI: articles—

Lane, John, "Pasolini's Road to Calvary," in Films and Filming (London), March 1963.

Hitchens, Gordon, "Pier Paolo Pasolini and the Art of Directing," in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1965.

Bragin, John, "Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poetry as a Compensation," in Film Society Review (New York), January, February, and March 1969.

Macdonald, Susan, "Pasolini: Rebellion, Art, and a New Society," in Screen (London), May/June 1969.

Armes, Roy, "Pasolini," in Films and Filming (London), June 1971.

Prono, F., "La Religione del suo tempo in Pier Paolo Paslini," in Cinema Nuovo (Turin), January/February 1972.

Bachmann, Gideon, "Pasolini in Persia: The Shooting of 1001 Nights ," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1973/74.

Di Giammatteo, F., editor of special issue "Lo Scandalo Pasolini," in Bianco e Nero (Rome), vol. 37, no. 1–4, 1976.

Barthes, Roland, "Sade-Pasolini," in Le Monde (Paris), 16 June 1976.

"Pier Paolo Pasolini Issues" of Etudes Cinématographiques (Paris), no. 109–111, 1976, and no. 112–114, 1977.

Escobar, R., "Pasolini e la dialettica dell'irrealizzabile," in Bianco e Nero (Rome), July/September 1983.

MacBean, J.R., "Between Kitsch and Fascism: Notes on Fassbinder, Pasolini, Homosexual Politics, the Exotic . . . ," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 13, no. 4, 1984.

Greene, N., "Reading Pasolini Today," in Quarterly Review of Film Studies (New York), Spring 1984.

Neupert, Richard, "A Cannibal's Text: Alternation and Embedding in Pasolini's Pigsty ," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), vol. 12, no. 3, 1988.

Joubert-Laurencin, H., "Portraits: Paolini-Freud, ou les chevilles qui enflent," in CinéAction (Toronto), January 1989.

Svenstedt, C.-H., and others, "Pasolini var samtida," in Chaplin (Stockholm), special section, vol. 32, 1990.

Cappabianca, A., "Pasolini: oltre l'urbano," in Filmcritica (Montepoulciano, Italy), vol. 42, June 1991.

Bruno, G., "Heresies: The Body of Pasolini's Semiotics," in Cinema Journal (Austin), vol. 30, Spring 1991.

Joubert-Laurencin, H., "1965–1975 Pier Paolo Pasolini, la divine théorie," in CinémAction (Conde-sur-Noireau), July 1991.

Orr, C., "The Politics of Film Form: Observations on Pasolini's Theory and Practice," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), Winter 1991.

Lapinski, Stan, "Il cinema di Pier Paolo Pasolini," in Skrien (Amsterdam), October-November 1993.

Filmihulu (Helsiniki), special section, no. 2, 1993.

Beylot, Pierre, "Pasolini, du réalisme au mythe," in CinémAction (Conde-sur-Noireau), January 1994.

Rohdie, Sam, "Pasolini, le populisme et le néoréalisme," in CinémAction (Conde-sur-Noireau), January 1994.

Gili, Jean A., "L'histoire du soldat," in Positif (Paris), December 1995.

Ciné-Bulles (Montreal), vol. 14, no. 4, Winter 1995.

Williama, Bruce, "A Transit to Significance: Poetic Discourse in Chantal Akerman's Toute une Nuit ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 23, July 1995.

Loiselle, Marie-Claude, "Poétique du montage," in 24 Images (Montreal), Summer 1995.

Mariniello, Silvestra, "La Résistance su corps dans l'image cinématographique: La mort, le myther et la sexualité dans le cinéma de Pasolini," in Cinémas (Montreal), vol. 7, no. 1–2, Autumn 1996

* * *

Pier Paolo Pasolini, poet, novelist, philosopher, and filmmaker, came of age during the reign of Italian fascism, and his art is inextricably bound to his politics. Pasolini's films, like those of his early apprentice Bernardo Bertolucci, began under the influence of neorealism. He also did early scriptwriting with Bolognini and Fellini. Besides these roots in neorealism, Pasolini's works show a unique blend of linguistic theory and Italian Marxism. But Pasolini began transcending the neorealist tradition even in his first film, Accattone (which means "beggar").

The relationship between Pasolini's literary work and his films has often been observed, and indeed Pasolini himself noted in an introduction to a paperback selection of his poetry that "I made all these films as a poet." Pasolini was a great champion of modern linguistic theory and often pointed to Roland Barthes and Erich Auerbach in discussing the films many years before semiotics and structuralism became fashionable. His theories on the semiotics of cinema centered on the idea that film was a kind of "real poetry" because it expressed reality with reality itself and not with other semiotic codes, signs, or systems.

Pasolini's interest in linguistics can also be traced to his first book of poetry, Poems of Casarsa , which is written in his native Friuli dialect. This early interest in native nationalism and agrarian culture is also a central element in Pasolini's politics. His first major poem, "The Ashes of Gramsci" (1954), pays tribute to Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist who founded the Italian Communist party. It created an uproar unknown in Italy since the time of D'Annunzio's poetry and was read by artists, politicians, and the general public.

The ideas of Gramsci coincided with Pasolini's own feelings, especially concerning that part of the working class known as the sub-proletariat, which Pasolini described as a prehistorical, pre-Christian, and pre-bourgeois phenomenon, one which occurs for him in the South of Italy (the Sud) and in the Third World.

This concern with "the little homelands," the indigenous cultures of specific regions, is a theme linking all of Pasolini's films, from Accattone to his final black vision, Salò. These marginal classes, known as cafoni (hicks or hillbillies), are among the main characters in Pasolini's novels Ragazzi de vita (1955) and A Violent Life (1959), and appear as protagonists in many of his films, notably Accattone, Mamma Roma, Hawks and Sparrows , and The Gospel according to Saint Matthew. To quote Pasolini: "My view of the world is always at bottom of an epical-religious nature: therefore even, in fact above all, in misery-ridden characters, characters who live outside of a historical consciousness, these epical-religious elements play a very important part."

In Accattone and The Gospel , images of official culture are juxtaposed against those of a more humble origin. The pimp of Accattone and the Christ of The Gospel are similar figures. When Accattone is killed at the end of the film, a fellow thief is seen crossing himself in a strange backward way, it is Pasolini's indictment of how Christianity has "contaminated" the subproletarian world of Rome. Marxism is never far away in The Gospel ; it is evident, for instance, in the scene where Satan, dressed as a priest, tempts Christ. In The Gospel , Pasolini has put his special brand of Marxism even into camera angles and has, not ironically, created one of the most moving and literal interpretations of the story of Christ. A recurrent motif in Pasolini's filmmaking, and especially prominent in Accattone and The Gospel , is the treatment of individual camera shots as autonomous units; the cinematic equivalent of the poetic image. It should also be noted that The Gospel according to Saint Matthew was filmed entirely in southern Italy.

In the 1960s Pasolini's films became more concerned with ideology and myth, while continuing to develop his epical-religious theories. Oedipus Rex (which has never been distributed in the United States) and Medea reaffirm Pasolini's attachment to the marginal and pre-industrial peasant cultures. These two films indict capitalism as well as communism for the destruction of these cultures, and the creation of a world which has lost its sense of myth.

In Teorema ("theorem" in Italian), which is perhaps Pasolini's most experimental film, a mysterious stranger visits a typical middle-class family, sexually seduces mother, father, daughter, and son, and destroys them. The peasant maid is the only character who is transformed because she is still attuned to the numinous quality of life which the middle class has lost. Pasolini has said about this film: "A member of the bourgeoisie, whatever he does, is always wrong."

Pigpen , which shares with Teorema the sulphurous volcanic location of Mount Etna, is a double film. The first half is the story or parable of a fifteenth-century cult of cannibals and their eventual destruction by the church. The second half concerns two former Nazis-turned-industrialists in a black comedy of rank perversion. It is the film closest in spirit to the dark vision of Salò. In the 1970s Pasolini turned against his elite international audience of intellectuals and film buffs and embraced the mass market with his "Trilogy of Life": Decameron, Canterbury Tales , and Arabian Nights. The Decameron was his first major European box-office hit, due mainly to its explicit sexual content. All three films are a celebration of Pasolini's philosophy of "the ontology of reality, whose naked symbol is sex." Pasolini, an avowed homosexual, in Decameron , and especially Arabian Nights , celebrates the triumph of female heterosexuality as the epitome of the life principle. Pasolini himself appears in two of these films, most memorably in the Decameron as Giotto's best pupil, who on completion of a fresco for a small town cathedral says, "Why produce a work of art, when it's so much better just to dream about it."

As a result of his growing political pessimism Pasolini disowned the "Trilogy" and rejected most of its ideas. His final film, Salò , is an utterly clinical examination of the nature of fascism, which for Pasolini is synonymous with consumerism. Using a classical, unmoving camera, Pasolini explores the ultimate in human perversions in a static, repressive style. Salò , almost impossible to watch, is one of the most horrifying and beautiful visions ever created on film. Pasolini's tragic, if not ironic, death in 1975 ended a visionary career that almost certainly would have continued to evolve.

—Tony D'Arpino

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: