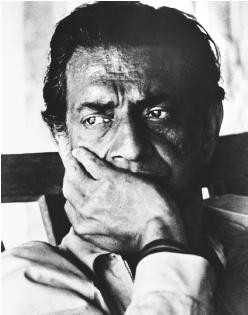

Satyajit Ray - Director

Nationality: Indian. Born: Calcutta, 2 May 1921. Education: Attended Ballygunj Government School; Presidency College, University of Calcutta, B.A. in economics (with honors), 1940; studied painting at University of Santiniketan, 1940–43. Family: Married Bijoya Das, 1949; one son. Career: Commercial artist for D. J. Keymer advertising agency, Calcutta, 1943; co-founder, Calcutta Film Society, 1947; met Jean Renoir making The River , 1950; completed first film, Pather Panchali , 1955; composed own music, from Teen Kanya (1961) on; made first film in Hindi (as opposed to Bengali), The Chess Players , 1977; editor and illustrator for children's magazine Sandesh , 1980s. Awards: Grand Prize, Cannes Festival, 1956, Golden Gate Award, San Francisco International Film Festival, 1957, Film Critics Award, Stratford Festival, 1958, and president of India Gold Medal, all for Pather Panchali ; Gold Lion, Venice Festival, 1957, Best Direction, San Francisco International Film Festival, 1958, and President of India Gold Medal, all for Aparajito; Selznick Award and Sutherland Trophy, 1960, for Apur Sansar; Silver Bear for Best Direction, Berlin Festival, for Mahanagar , 1964, and for Charulata , 1965; Special Award of Honour, Berlin Festival, 1966; Decorated Order Yugoslav Flag, 1971; Golden Bear Award, Berlin Film Festival, 1973, for Distant Thunder; D.Litt, Oxford University, 1978; life fellow, British Film Institute, 1983; Legion of Honour, France, 1989; Indian Awards, Best Picture and Best Director, 1991, for Agantuk; Academy Award for lifetime achievement in cinema, 1992. Died: Of heart failure, 23 April 1992, in Calcutta.

Films as Director and Scriptwriter:

- 1955

-

Pather Panchali ( Father Panchali ) (+ pr)

- 1956

-

Aparajito ( The Unvanquished ) (+ pr)

- 1957

-

Parash Pathar ( The Philosopher's Stone )

- 1958

-

Jalsaghar ( The Music Room ) (+ pr)

- 1959

-

Apur Sansar ( The World of Apu ) (+ pr)

- 1960

-

Devi ( The Goddess ) (+ pr, mus)

- 1961

-

Teen Kanya ( Two Daughters ) (+ pr); Rabindranath Tagore (doc)

- 1962

-

Abhijan ( Expedition ); Kanchanjanga (+ pr)

- 1963

-

Mahanagar ( The Big City )

- 1964

-

Charulata ( The Lonely Wife )

- 1965

-

Kapurush-o-Mahapurush ( The Coward and the Saint ); Two (short)

- 1966

-

Nayak ( The Hero )

- 1967

-

Chiriakhana ( The Zoo )

- 1969

-

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne ( The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha )

- 1970

-

Pratidwandi ( The Adversary ); Aranyer Din Ratri ( Days and Nights in the Forest )

- 1971

-

Seemabaddha ; Sikkim (doc)

- 1972

-

The Inner Eye (doc)

- 1973

-

Asani Sanket ( Distant Thunder )

- 1974

-

Sonar Kella ( The Golden Fortress )

- 1975

-

Jana Aranya ( The Middleman )

- 1976

-

Bala (doc)

- 1977

-

Shatranj Ke Khilari ( The Chess Players )

- 1978

-

Joi Baba Felunath ( The Elephant God )

- 1979

-

Heerak Rajar Deshe ( The Kingdom of Diamonds )

- 1981

-

Sadgati ( Deliverance ) (for TV); Pikoo (short)

- 1984

-

Ghare Bahire ( The Home and the World ) (+ pr, mus)

- 1989

-

Ganashatru ( An Enemy of the People )

- 1990

-

Shakha Proshakha ( Branches of the Tree )

- 1991

-

Agantuk ( The Visitor )

Publications

By RAY: books—

Our Films, Their Films , New Delhi, 1977.

The Chess Players and Other Screenplays , London, 1989.

My Years with APU , New York, 1994.

By RAY: articles—

"A Long Time on the Little Road," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1957.

"Satyajit Ray on Himself," in Cinema (Beverly Hills), July/Au-gust 1965.

"From Film to Film," in Cahiers du Cinéma in English (New York), no. 3, 1966

Interview, in Film Makers on Filmmaking , by Harry M. Geduld, Bloomington, Indiana, 1967.

Interview, in Interviews with Film Directors , edited by Andrew Sarris, New York, 1967.

Interview with J. Blue, in Film Comment (New York), Summer 1968.

"Conversation with Satyajit Ray," with F. Isaksson, in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1970.

"Ray's New Trilogy," an interview with C. B. Thomsen, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1972/73.

"Dialogue on Film: Satyajit Ray," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), July/August 1978.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), May 1979.

Interview with U. Gupta, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 12, no. 1, 1982.

"Under Western Eyes," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1982.

"Bridging the Home and the World," an interview with A. Robinson, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), September 1984.

Interview with Charles Tesson, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July/August 1987.

Interview with Derek Malcolm, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1989.

Time Out (London), 29 April 1992.

"To Western Audiences, the Filmmaker Satyajit Ray Is Synonymous with Indian Cinema," an interview with Gowri Ramnarayan, in Interview , June 1992.

On RAY: films—

Satyajit Ray , 1982.

Satyajit Ray: Introspections , 1991.

On RAY: books—

Seton, Marie, Portrait of a Director , Bloomington, Indiana, 1970.

Wood, Robin, The Apu Trilogy , New York, 1971.

Taylor, John Russell, Directors and Directions: Cinema for '70s , New York, 1975.

Rangoonwalla, Firoze, Satyajit Ray's Art , Shahdara, Delhi, 1980.

Satyajit Ray: An Anthology , edited by Chidananda Das Gupta, New Delhi, 1981.

Willemen, Paul, and Behroze Gandhy, Indian Cinema , London, 1982.

Armes, Roy, Third World Filmmaking and the West , Berkeley, 1987.

Nyce, Ben, Satyajit Ray: A Study of His Films , New York, 1988.

Robinson, Andrew, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye , London, 1989.

Tesson, Charles, Satyajit Ray , Paris, 1992.

Sarkar, Bidyut, World of Satyajit Ray , UBS Publishers, 1992.

Banerjee, Tarapada, Satyajit Ray: A Portrait in Black and White , New York, 1993.

Moras, Chris, Creativity and Its Contents , Chester Springs, Pennsyl-vania, 1995.

Banerjee, Surabhi, Satyajit Ray: Beyond the Frame , Allied Publish-ers, 1996.

Das, Santi, editor, Satyajit Ray: An Intimate Master , Allied Publish-ers, 1998.

On RAY: articles—

Gray, H., "The Growing Edge: Satyajit Ray," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley, California), Winter 1958.

Rhode, Eric, "Satyajit Ray: A Study," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1961.

Stanbrook, Alan, "The World of Ray," in Films and Filming (London), November 1965.

Hrusa, B., "Satyajit Ray: Genius behind the Man," in Film (London), Winter 1966.

Glushanok, Paul, "On Ray," in Cineaste (New York), Summer 1967.

Malik, A., "Satyajit Ray and the Alien," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1967/68.

Mehta, V., "Profiles," in New Yorker , 21 March 1970.

Thomsen, Christian Braad, "Ray's New Trilogy," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1972/73.

Dutta, K., "Cinema in India: An Interview with Satyajit Ray's Cinematographers," in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), January 1975.

Hughes, J., "A Voyage in India: Satyajit Ray," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1976.

" Pathar Panchali Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 1 Febru-ary 1980.

Armes, Roy, "Satyajit Ray: Astride Two Cultures," in Films and Filming (London), August 1982.

Robinson, A., "Satyajit Ray at Work," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), September 1983.

Ray, B., "Ray off Set," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1983/84.

Das Gupta, Chidananda, and Andrew Robinson, "A Passage from India," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1985.

Dissanyake, W., "Art, Vision, and Culture: Sayajit Ray's Apu Trilogy Revisited," in East-West Film Journal (Honolulu), vol. 1, December 1986.

Gehler, F., "Wie der Tempel von Konarak," in Film und Fernsehen (Potsdam, Germany), vol. 16, July 1988.

Robinson, Andrew, "The Music Room," in Sight and Sound (Lon-don), Autumn 1989.

Armand, M., "Satyajit Ray au present," in Cahiers du Cinéma , July/August 1990.

Jivani, A., "Ray of Hope," in Time Out (London), 24 April 1991.

Sengupta, Shuddhabarata, "Reflections on Satyajit Ray," World Press Review , April 1992.

Schickel, Richard, "Days and Nights at the Art House," in Film Comment , May/June 1992.

Andersson, K., "Satyajit Ray," in Cinema Papers , May/June 1992.

Chatterjee, D., "Entretien avec Satyajit Ray," in Cahiers du Cinéma , June 1992.

Grafe, L., and O. Moller, obituary, in Film-Dienst (Köln), vol. 45, 12 May 1992.

McBride, J., and D. Young, obituary, in Variety , 27 April 1992.

Obituary, in Filmnews , vol. 22, no. 4, May 1992.

Niogret, H., and M. Ciment, "Les espaces de Satyajit Ray," in Positif (Paris), June 1992.

Obituary, in EPD Film (Frankfurt), vol. 4, June 1992.

Sight and Sound (London), special section, vol. 2, August 1992.

Bonneville, L., in Séquences (Haute-Ville, Québec), November 1992.

Heifetz, H., "Mixed Music: In Memory of Satyajit Ray," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 14, 1993.

Mensuel du Cinéma (Paris), special section, January 1993.

Andersson, K., "Lo scambio di culture nell'opera di Satyajit Ray," in Cinema Nuovo (Rome), vol. 42, January-February 1993.

Positif (Paris), special section, no. 399, May 1994.

Ganguly, Keya, "Carnal Knowledge: Visuality and the Modern in Charulata," in Camera Obscura (Bloomington), no. 37, Janu-ary 1996.

Van der Heide, Bill, "Experiencing India: A Personal History," in Media International Australia (North Ryde, NSW), no. 80, May 1996.

* * *

From the beginning of his career as a filmmaker, Satyajit Ray was interested in finding ways to reveal the mind and thoughts of his characters. Because the range of his sympathy was wide, he has been accused of softening the presence of evil in his cinematic world. But a director who aims to represent the currents and cross-currents of feeling within people is likely to disclose to viewers the humanness even in reprehensible figures. In any case, from the first films of his early period, Ray devised strategies for rendering inner lives; he simplified the surface action of the film so that the viewer's attention travels to (1) the reaction of people to one another, or to their environments, (2) the mood expressed by natural scenery or objects, and (3) music as a clue to the state of mind of a character. In the Apu Trilogy the camera often stays with one of two characters after the other character exits the frame to see their silent response. Or else, after some significant event in the narrative, Ray presents correlatives of that event in the natural world. When the impoverished wife in Pather Panchali receives a postcard bearing happy news from her husband, the scene dissolves to water skates dancing on a pond. As for music, in his films Ray commissioned compositions from India's best classical musicians—Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan, Ali Akbar Khan—but after Teen Kanya composed his own music and progressed towards quieter indication through music of the emotional experience of his characters.

Ray's work can be divided into three periods on the basis of his cinematic practice: the early period, 1955–66, from Pather Panchali through Nayak ; the middle period, 1969–1977, from Googy Gyne Bagha Byne through Shatranj Ke Khilari ; and the final period, from Joy Baba Felunath and through his final film Agantuk , in 1991. The early period is characterized by thoroughgoing realism: the mise-enscène are rendered in deep focus; long takes and slow camera movements prevail. The editing is subtle, following shifts of narrative interest and cutting on action in the Hollywood style. Ray's emphasis in the early period on capturing reality is obvious in Kanchanjangha , in which 100 minutes in the lives of characters are rendered in 100 minutes of film time. The Apu Trilogy, Parash Pather, Jalsaghar , and Devi all exemplify what Ray had learned from Hollywood's studio era, from Renoir's mise-en-scène, and from the use of classical music in Indian cinema. Charulata affords the archetypal example of Ray's early style, with the decor, the music, the long takes, the activation of various planes of depth within a composition, and the reaction shots all contributing significantly to a representation of the lonely wife's inner conflicts. The power of Ray's early films comes from his ability to suggest deep feeling by arranging the surface elements of his films unemphatically.

Ray's middle period is characterized by increasing complexity of style; to his skills at understatement Ray adds a sharp use of montage. The difference in effect between an early film and a middle film becomes apparent if one compares the early Mahanagar with the middle Jana Aranya , both films pertaining to life in Calcutta. In Mahanagar , the protagonist chooses to resign her job in order to protest the unjust dismissal of a colleague. The film affirms the rightness of her decision. In the closing sequence, the protagonist looks up at the tall towers of Calcutta and says to her husband so that we believe her, "What a big city! Full of jobs! There must be something somewhere for one of us!" Ten years later, in Jana Aranya , it is clear that there are no jobs and that there is precious little room to worry about niceties of justice and injustice. The darkness running under the pleasant facade of many of the middle films seems to derive from the turn in Indian politics after the death of Nehru. Within Bengal, many ardent young people joined a Maoist movement to destroy existing institutions, and more were themselves destroyed by a ruthless police force. Across India, politicians abandoned Nehru's commitment to a socialist democracy in favor of a scramble for personal power. In Seemabaddha or Aranyer Din Ratri Ray's editing is sharp but not startling. In Shatranj Ke Khilari , on the other hand, Ray's irony is barely restrained: he cuts from the blue haze of a Nawab's music room to a gambling scene in the city. In harsh daylight, commoners lay bets on fighting rams, as intent on their gambling as the Nawab was on his music.

Audiences in India who responded warmly to Ray's early films have sometimes been troubled by the complexity of his middle films. A film like Shatranj Ke Khilari was expected by many viewers to reconstruct the splendors of Moghul India as the early Jalsaghar had reconstructed the sensitivity of Bengali feudal landlords and Charulata the decency of upper class Victorian Bengal. What the audience found instead was a stern examination of the sources of Indian decadence. According to Ray, the British seemed less to blame for their role than the Indians who demeaned themselves by colluding with the British or by ignoring the public good and plunging into private pleasures. Ray's point of view in Shatranj was not popular with distributors and so his first Hindi film was denied fair exhibition in many cities in India.

Ray's concluding style, most evident in the short features Pikoo and Sadgati , pays less attention than earlier to building a stable geography and a firm time scheme. The exposition of characters and situations is swift: the effect is of great concision. In Pikoo , a young boy is sent outside to sketch flowers so that his mother and her lover can pursue their affair indoors. The lover has brought along a drawing pad and colored pens to divert the boy. The boy has twelve colored pens in his packet with which he must represent on paper the wealth of colors in nature. In a key scene (lasting ten seconds) the boy looks at a flower, then down at his packet for a matching color. Through that action of the boy's looking to match the world with his means, Ray suggests the striving in his own work to render the depth and range of human experience.

In focussing on inner lives and on human relations as the ground of social and political systems, Ray continued the humanist tradition of Rabindranath Tagore. Ray studied at Santiniketan, the university founded by Tagore, and was close to the poet during his last years. Ray once acknowledged his debt in a lyrical documentary about Tagore, and through the Tagore stories on which he based his films Teen Kanya, Charulata , and Ghare Bahire. As the poet Tagore was his example, Ray has become an example to important younger filmmakers (such as Shyam Benegal, M. S. Sathyu, G. Aravindan), who have learned from him how to reveal in small domestic situations the working of larger political and cultural forces.

—Satti Khanna

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: