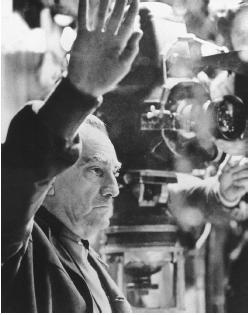

Luchino Visconti - Director

Nationality: Italian. Born: Count Don Luchino Visconti di Modrone in Milan, 2 November 1906. Education: Educated at private schools in Milan and Como; also attended boarding school of the Calasanzian Order, 1924–36. Military Service: Served in Reggimento Savoia Cavalleria, 1926–28. Career: Stage actor and set designer, 1928–29; moved to Paris, assistant to Jean Renoir, 1936–37; returned to Italy to assist Renoir on La Tosca , 1939; directed first film, Ossessione , 1942; directed first play, Cocteau's Parenti terrible , Rome, 1945; directed first opera, La vestale , Milan, 1954; also ballet director, 1956–57. Awards: International Prize, Venice Festival, for La terra trema , 1948; 25th Anniversary Award, Cannes Festival, 1971. Died: 17 March 1976.

Films as Director:

- 1942

-

Ossessione (+ co-sc)

- 1947

-

La terra trema (+ sc)

- 1951

-

Bellissima (+ co-sc); Appunti su un fatto di cronaca (second in series Documento mensile )

- 1953

-

"We, the Women" episode of Siamo donne (+ co-sc)

- 1954

-

Senso (+ co-sc)

- 1957

-

Le notti bianche ( White Nights ) (+ co-sc)

- 1960

-

Rocco e i suoi fratelli ( Rocco and His Brothers ) (+ co-sc)

- 1962

-

"Il lavoro (The Job)" episode of Boccaccio '70 (+ co-sc)

- 1963

-

Il gattopardo ( The Leopard ) (+ co-sc)

- 1965

-

Vaghe stelle dell'orsa ( Of a Thousand Delights ; Sandra ) (+ co-sc)

- 1967

-

"Le strega bruciata viva" episode of Le streghe ; Lo straniero ( L'Etranger ) (+ co-sc)

- 1969

-

La caduta degli dei ( The Damned ; Götterdämmerung ) (+ co-sc)

- 1970

-

Alla ricerca di Tadzio

- 1971

-

Morte a Venezia ( Death in Venice ) (+ pr, co-sc)

- 1973

-

Ludwig (+ co-sc)

- 1974

-

Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (+ co-sc)

- 1976

-

L'innocente ( The Innocent ) (+ co-sc)

Other Films:

- 1936

-

Les Bas-fonds (Renoir) (asst d)

- 1937

-

Une Partie de campagne (Renoir) (asst d) (released 1946)

- 1940

-

La Tosca (Renoir) (asst d)

- 1945

-

Giorni di gloria (De Santis) (asst d)

Publications

By VISCONTI: books—

Senso , Bologna, 1955.

Le notti bianche , Bologna, 1957.

Rocco e i suoi fratelli , Bologna, 1961.

Il gattopardo , Bologna, 1963.

Vaghe stelle dell'orsa ( Sandra ), Bologna, 1965.

Three Screenplays , New York, 1970.

Morte a Venezia , Bologna, 1971.

Il mio teatro , in two volumes, Bologna, 1979.

By VISCONTI: articles—

"Il cinéma antropomorfico," in Cinema (Rome), 25 September 1943.

" La terra trema ," in Bianco e Nero (Rome), March 1951.

" Marcia nuziale ," in Cinema Nuovo (Turin), 1 May 1953.

Interview with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Jean Domarchi, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1959.

"The Miracle That Gave Men Crumbs," in Films and Filming (London), January 1961.

"Drama of Non-Existence," in Cahiers du Cinéma in English (New York), no. 2, 1966.

"Violence et passion," special Visconti issue of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), June 1975.

Interview with Peter Brunette, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1986/87.

On VISCONTI: books—

Pellizzari, Lorenzo, Luchino Visconti , Milan, 1960.

Baldelli, Pio, I film di Luchino Visconti , Manduria, Italy, 1965.

Guillaume, Yves, Visconti , Paris, 1966.

Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, Luchino Visconti , New York, 1968.

Ferrero, Adelio, editor, Visconti: Il cinema , Modena, 1977.

Tornabuoni, Lietta, editor, Album Visconti , foreward by Michelangelo Antonioni, Milan, 1978.

Stirling, Monica, A Screen of Time: A Study of Luchino Visconti , New York, 1979.

Servadio, Gaia, Luchino Visconti: A Biography , London, 1981.

Bencivenni, Alessandro, Luchino Visconti , Florence, 1982.

Tonetti, Claretta, Luchino Visconti , Boston, 1983.

Ishaghpour, Youssef, Luchino Visconti: Le sens de l'image , Paris, 1984.

Sanzio, Alain, and Paul-Louis Thirard, Luchino Visconti: Cinéaste , Paris, 1984.

De Giusti, Luciano, I film di Luchino Visconti , Rome, 1985.

Mancini, Elaine, Luchino Visconti: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1986.

Villien, Bruno, Visconti , Paris, 1986.

Schifano, Laurence, Luchino Visconti: Les feux de la passion , Paris, 1987; published as Luchino Visconti: The Flames of Passion , London, 1990.

On VISCONTI: articles—

Renzi, Renzo, "Mitologia e contemplasione in Visconti, Ford e Eisenstein," in Bianco e Nero (Rome), February 1949.

Demonsablon, Philippe, "Notes sur Visconti," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1954.

Lane, John Francis, "The Hurricane Visconti," in Films and Filming (London), December 1954.

Castello, Giulio, "Luchino Visconti," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1956.

Lane, John Francis, "Visconti—The Last Decadent," in Films and Filming (London), July 1956.

Dyer, Peter John, "The Vision of Visconti," in Film (London), March/April 1957.

Poggi, Gianfranco, "Luchino Visconti and the Italian Cinema," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1960.

"Visconti Issue" of Premier Plan (Paris), May 1961.

"Visconti Issue" of Etudes Cinématographiques (Paris), no. 26–27, 1963.

Elsaesser, Thomas, "Luchino Visconti," in Brighton (London), February 1970.

"Visconti Issue" of Cinema (Rome), April 1970.

Aristarco, Guido, "The Earth Still Trembles," in Films and Filming (London), January 1971.

Korte, Walter, "Marxism and Formalism in the Films of Luchino Visconti," in Cinema Journal (Evanston, Illinois), Fall 1971.

Cabourg, J., "Luchino Visconti, 1906–1976," in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 1 and 15 March 1977.

Sarris, Andrew, "Luchino Visconti's Legacy," in The Village Voice (New York), 15 January 1979.

Rosi, Francesco, "En travaillant avec Visconti: sur le tournage de La Terra trema ," in Positif (Paris), February 1979.

Lyons, D., "Visconti's Magnificient Obsessions," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1979.

Special issue of Castoro Cinema (Firenze), no. 98, 1982.

Graham, A., "The Phantom Self," in Film Criticism (New York), Fall 1984.

Gerosa, M., "Visconti e i suoi attori," in Cinema Nuovo (Rome), vol. 36, no. 308–309, August-October 1987.

Aristarco, Guido, "Luchino Visconti: Critic or Poet of Decadence?," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), Spring 1988.

Filmcritica (Montepoulciano), vol. 42, no. 419, November 1991.

Aristarco, G., "Der späte Visconti zuischen Wagner und Mann," in Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), vol. 20, no. 5, October 1992.

Schleifer, E., "Das Ende des 'Flickerlteppichs,"' in Film-Dienst (Cologne), vol. 46, no. 6, 16 March 1993.

Schneider, Roland, "Visconti ou la déviation esthétique," in CinémAction (Conde-sur-Noireau), no. 70, January 1994.

Bertellini, Giorgio, "A Battle d'arrière-garde: Notes on Decadence in Luchino Visconti's Death in Venice ," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), vol. 50, no. 4, Summer 1997.

Liandrat-Guiges, Suzanne, "Le corps à corps des images dans l'oeuvre de Visconti," in Cinémas (Montreal), vol. 8, no. 1–2, Autumn 1996.

* * *

The films of Luchino Visconti are among the most stylistically and intellectually influential of postwar Italian cinema. Born a scion of ancient nobility, Visconti integrated the most heterogeneous elements of aristocratic sensibility, and taste with a committed Marxist political consciousness, backed by a firm knowledge of Italian class structure. Stylistically, his career follows a trajectory from a uniquely cinematic realism to an operatic theatricalism, from the simple quotidian eloquence of modeled actuality to the heightened effect of lavishly appointed historical melodramas. His career fuses these interests into a mode of expression uniquely Viscontian, prescribing a potent, double-headed realism. Visconti turned out films steadily but rather slowly from 1942 to 1976. His obsessive care with narrative and filmic materials is apparent in the majority of his films.

Whether or not we choose to view the wartime Ossessione as a precursor or a determinant of neorealism, or merely as a continuation of elements already present in Fascist period cinema, it is clear that the film remarkably applies a realist mise-en-scène to the formulaic constraints of the genre film. With major emendations, the film is, following a then-contemporary interest in American fiction of the 1930s, a treatment (the second and best) of James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice. In it the director begins to explore the potential of a long-take style, undoubtedly influenced by Jean Renoir, for whom Visconti had worked as assistant. Having met with the disapproval of the Fascist censors for its depiction of the shabbiness and desperation of Italian provincial life, Ossessione was banned from exhibition.

For La terra trema , Visconti further developed those documentary-like attributes of story and style generally associated with neorealism. Taken from Verga's late nineteenth-century masterpiece I malavoglia , the film was shot entirely on location in Sicily and employed the people of the locale, speaking in their native dialect, as actors. Through them, Visconti explores the problems of class exploitation and the tragedy of family dissolution under economic pressure. Again, a mature long-shot/long-take style is coupled with diverse, extensive camera movements and well-planned actor movements to enhance the sense of a world faithfully captured in the multiplicity of its activities. The extant film was to have become the first episode of a trilogy on peasant life, but the other two parts were never filmed.

Rocco e i suoi fratelli , however, made over a dozen years later, continues the story of this Sicilian family, or at least one very much like it. Newly arrived in Milan from the South, the Parandis must deal with the economic realities of their poverty as well as survive the sexual rivalries threatening the solidarity of their family unit. The film is episodic in nature, affording time to each brother's story (in the original version), but special attention is given to Rocco, the forebearing and protective brother who strives at all costs to keep the group together, and Simone, the physically powerful and crudely brutal one, who is unable to control his personal fears, insecurities, and moral weakness. Unable to find other work, they both drift into prize fighting, viewed here as class exploitation. Jealousy over the prostitute Nadia causes Simone to turn his fists against his brother, then to murder the woman. But Rocco, impelled by strong traditional ties, would still act to save Simone from the police. Finally, the latter is betrayed to the law by Ciro, the fourth youngest and a factory worker who has managed to transfer some of his familial loyalty to a social plane and the labor union. Coming full circle from La terra trema , Luca, the youngest, dreams of a day when he will be able to return to the Southern place of his birth. Rocco is perhaps Visconti's greatest contribution to modern tragedy, crafted along the lines of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams (whose plays he directed in Italy). The Viscontian tragedy is saturated with melodramatic intensity, a stylization incurring more than a suggestion of decadent sexuality and misogyny. There is also, as in other Visconti works, a rather ambiguous intimation of homosexuality (here between Simone and his manager.)

By Senso Visconti had achieved the maturity of style that would characterize his subsequent work. With encompassing camera movements—like the opening shot, which moves from the stage of an opera house across the audience, taking in each tier of seats where the protest against the Austrians will soon erupt—and with a melodramatic rendering of historical fact, Visconti begins to mix cinematic realism with compositional elegance and lavish romanticism. Against the colorful background of the Risorgimento, he paints the betrayal by an Austrian lieutenant of his aristocratic Italian mistress who, in order to save him, has compromised the partisans. The love story parallels the approaching betrayal of the revolution by the bourgeois political powers.

Like Gramsci, who often returned to the contradictions of the Risorgimento as a key to the social problems of the modern Italian state, Visconti explores that period once more in Il gattopardo , from the Lampedusa novel. An aristocratic Sicilian family undergoes transformation as a result of intermarriage with the middle-class at the same time that the Mezzogiorno is undergoing unification with the North. The bourgeoisie, now ready and able to take over from the dying aristocracy, usurps Garibaldi's revolution; in this period of transformismo , the revolutionary process will be assimilated into the dominant political structure and defused.

Still another film that focuses on the family unit as a barometer of history and changing society is La caduta degli dei. This treatment of a German munitions industry family (much like Krupp) and its decline into betrayal and murder in the interests of personal gain and the Nazi state intensifies and brings up-to-date an examination of the social questions of the last mentioned films. Here again a meticulous, mobile camera technique sets forth and stylistically typifies a decadent, death-surfeited culture.

Vaghe stelle dell'orsa removes the critique of the family from the social to the psychoanalytic plane. While death or absence of the father and the presence of an uprising surrogate is a thematic consideration in several Visconti films, he here explores it in conjunction with Freudian theory in this deliberate yet entirely transmuted retelling of the Elektra myth. We are never completely aware of the extent of the relationship between Sandra and her brother, and the possibility of past incest remains distinct. Both despise their stepfather Gilardini, whom they accuse of having seduced their mother and having denounced their father, a Jew, to the Fascists. Sandra's love for and sense of solidarity with her brother follows upon a racial solidarity with her father and race, but Gianni's love, on the other hand, is underpinned by a desire for his mother, transferred to Sandra. Nevertheless, dramatic confrontation propels the dialectical investigations of the individual's position with respect to the social even in this, Visconti's most densely psychoanalytic film.

Three films marking a further removal from social themes and observation of the individual, all literary adaptations, are generally felt to be his weakest: Le notte bianche from Dostoevski's White Nights sets a rather fanciful tale of a lonely man's hopes to win over a despairing woman's love against a decor that refutes, in its obvious, studio-bound staginess, Visconti's concern with realism and material verisimilitude. The clear inadequacy of this Livornian setting, dominated by a footbridge upon which the two meet and the unusually claustrophobic spatiality that results, locate the world of individual romance severed from large social and historical concerns in an inert, artificial perspective that borders on the hallucinatory. He achieves similar results with location shooting in Lo straniero , where—despite alterations of the original Camus—he perfectly captures the difficult tensions and tones of individual alienation by utilizing the telephoto lens pervasively. Rather than provide a suitable Viscontian dramatic space rendered in depth, it reduces Mersault to the status of a Kafkaesque insect-man observed under a microscope. Finally, Morte a Venezia , based on the fiction of Thomas Mann, while among Visconti's most formally beautiful productions, is one of his least critically successful. The baroque elaboration of mise-en-scène and camera work does not rise above self-pity and self-indulgence, and is cut off from social context irretrievably.

—Joel Kanoff

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: