CANTINFLAS - Actors and Actresses

Nationality: Mexican. Born: Mario Moreno Reyes in Ciudad de los Palacios, 12 August 1911. Education: Studied at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in the school of medicine. Family: Married Valentina Zubareff, 1937 (died 1966), son: Mario Arturo Moreno Ivanova. Career: 1930—began working in variety theaters, using name Cantinflas to hide identity from family; 1936—first film role as comic in No te engañes corazón ; 1940—became leading comic figure of Spanish-language cinema with lead role in Ahí está el detalle ; 1941—founded Posa Films production company and produced Ni sangre ni arena ; began lifelong professional relationship with the director Miguel M. Delgado after first film together, El gendarme desconocido ; 1956—became known internationally after role as Passepartout in Around the World in Eighty Days ; 1960—commercial and critical failure of Pepe led to his departure from Hollywood and return to Mexico; 1981—final feature film, after which he concentrated on philanthropic interests. Awards: Special Prize, Ariel Awards, Mexico, for "work on behalf of the Mexican

cinema," 1950–51; Golden Globe for Best Actor, for Around the World in Eighty Days , 1956; Special Award, Golden Globes, 1960; Special Prize, Mexican Silver Goddesses, 1969; named "symbol of peace and happiness of the Americas," by the Organization of American States, 1983; Diploma of Honor, Inter-American Council of Music, 1983; honored for lifelong contribution to Mexican cinema, by the Mexican Academy of Cinemagraphic Arts and Sciences, 1988. Died: Of lung cancer, in Mexico City, 20 April 1993.

Films as Actor:

- 1936

-

No te engañes corazón ( Don't Deceive Yourself, My Heart ) (Torres)

- 1937

-

Así es mi tierra! (Boytler); Aguila o sol (Boytler)

- 1939

-

Siempre listo en las tinieblas (Rivero—short); Jengibre contra dinamita (Rivero—short); El signo de la muerte (Urueta)

- 1940

-

Ahí está el detalle ( There Is the Detail ; Here's the Point ) (Oro) (as himself); Cantiflas y su prima (Toussain—short); Cantiflas boxeador ( Cantinflas the Boxer ) (Rivero—short); Cantiflas ruletero (Rivero—short)

- 1941

-

Ni sangre ni arena ( Neither Blood Nor Sand ) (Galindo) (+ pr); El gendarme desconocido (Delgado) (as 77)

- 1942

-

Los tres mosqueteros ( The Three Musketeers ) (Delgado) (as D'Artagnan); El circo (Delgado)

- 1943

-

Romeo y Julieta ( Romeo and Juliet ) (Delgado) (as Romeo)

- 1944

-

Gran hotel (Delgado)

- 1945

-

Un día con el diablo (Delgado)

- 1946

-

Soy un prófugo (Delgado)

- 1948

-

El supersabio (Delgado)

- 1949

-

Puerta . . . joven (Delgado); El mago

- 1950

-

El siete machos (Delgado); El bombero atómico ( The Atomic Fireman ) (Delgado)

- 1951

-

Si yo fuera diputado (Delgado)

- 1952

-

El señor fotógrafo (Delgado)

- 1953

-

Caballero a la medida (Delgado)

- 1954

-

Abajo el telón (Delgado)

- 1956

-

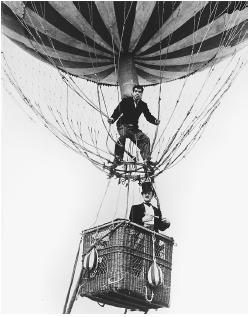

El bolero de Raquel (Delgado); Around the World in Eighty Days (Anderson) (as Passepartout)

- 1957

-

Les Bijoutiers du clair de lune ( The Night Heaven Fell ; Heaven Fell that Night ) (Vadim) (as Alfonso)

- 1958

-

Ama a tu prójimo (Demicheli); Sube y bajo (Delgado); Agguato a Tangeri ( Trapped in Tangiers ) (Freda)

- 1960

-

Pepe (Sidney) (title role); El analfabeto (Delgado) (as Inocencio Prieto y Calvo)

- 1962

-

El extra (Delgado) (Rogaciano)

- 1963

-

Entrega immediata (Delgado) (as Feliciano)

- 1964

-

El padrecito (Delgado) (as Padre Sebas)

- 1965

-

El señor doctor (Delgado) (as Dr. Medina)

- 1966

-

Su exelencia (Delgado)

- 1968

-

Por mis pistolas (Delgado) (as Fidenco)

- 1969

-

Don Quijote sin mancha (Delgado)

- 1970

-

El profe (Delgado)

- 1972

-

Don Quijote cabalga de nuevo (Delgado) (as Sancho Panza)

- 1976

-

El ministro y Yo (Delgado)

- 1978

-

El patrullero 777 ( Patrol Car 777 ) (Delgado)

- 1981

-

El Barrendero (Delgado)

- 1985

-

Mexico . . . Estamos Contigo (for TV)

Publications

By CANTINFLAS: book—

Cantiflas: Apología de un humilde , Mexico, n.d.

On CANTINFLAS: books—

García Riera, Emilio, Historia documental del cine mexicano , vols. 1–9, Mexico, 1969–78.

Ayala Blanco, Jorge, La aventura del cine mexicano , Mexico, 1979.

Mora, Carl J., Mexican Cinema: Reflections of a Society 1896–1980 , Berkeley, 1982.

Reachi, Santiago, La Revolución, Cantinflas y JoLoPo , Mexico City, 1982.

Ayala Blanco, Jorge, La búsqueda del cine mexicano , Mexico City, 1986.

Ayala Blanco, Jorge, La condición del cine mexicano , Mexico City, 1986.

De los Reyes, Aurelia, Medio siglo de cine mexicano (1896–1947) , Mexico City, 1987.

On CANTINFLAS: articles—

Time (New York), 26 August 1940.

Oliver, M. R., "Cantinflas," in Hollywood Quarterly , April 1947.

Ross, B., "Mexico's Chaplin," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1948.

Current Biography 1953 , New York, 1953.

"The Comedy of Cantinflas," in Films in Review (New York), January 1958.

Zunser, J., "Mexico's Millionaire Mirthquake," in Cue , 23 August 1958.

Butler, Ron, "Cantinflas: Mexico's Prince of Comedy," in Américas , April 1981.

Mejias-Rentas, Antonio, "Cantinflas Given D.C. Tribute," in Nuestro , June/July 1983.

García Marruz, Fina, "Cantinflas," in Cine Cubano (Havana), no. 111, 1985.

Obituary in New York Times , 22 April 1993.

Obituary in Variety (New York), 26 April 1993.

"OAS Bids Farewell to Cantinflas," in Américas , May/June 1993. Stavans, Ilan, "The Riddle of Cantinflas," in Transition , no. 67, 1995.

* * *

The best-known figure of Spanish-language cinema, Cantinflas gained international recognition through his rendering of a purely local character. The Pelado is native to Mexico City's slums—a lumpen-proletarian created by rapid, unplanned, and uncontrollable urbanization, the clash of classes in a dependent and underdeveloped society, and the racial mixing and antagonism of Indians and Europeans. Streetwise as only the powerless learn to become, the pelado relies on wit and guile in dealing with the state apparatus—law, for instance—which oppresses rather than protects him. Cantinflas's peladito was a comic variant of this character but the actor's lack of a critical class consciousness led in the end to his acceptance of the very forces that he had built his career on attacking.

Literally, pelado means stripped clean, broke. Cantinflas himself defined his "prototype of the humble people from the urban barrio " in this way: "superficially educated and practically non-existent socially, but with a highly developed ingenuity (a Mexican characteristic), a formidable astuteness—and a large, gentle, and open heart." Confronted with the rich and powerful, Cantinflas's peladito delights in turning the tables and confusing them with their own tools of domination.

Language—the instrument of the educated—is one of the ways the privileged classes maintain their position, but it is also a front on which the peladito excels. Cantinflas's enormous gift for impromptu verbal invention was the very essence of his comedy—requiring, for example, that he be allowed to improvise fully on scripts. In Mexico, to cantinflear has come to mean to talk a lot and say nothing, while the noun cantinflas means lovable clown. As Cantinflas put it, when an explanation is demanded "by the policeman whose hat you stepped on or the boss whose shirt you just spilled catsup down, the pelado's defense is to talk, talk, talk."

In Cantinflas's early films this nonsensical double-talk was used to criticize forms of social control—for example, when he confused a courtroom full of lawyers, infecting them with his incoherent verbiage in Ahí está el detalle . In the later works, however, this critical attitude toward the use and abuse of language was replaced with word games which essentially denied the existence of social problems. In his last several movies Cantinflas became openly reactionary, taking on social roles he had earlier criticized, such as priest, doctor, and politician. Under the guise of being nonideological, Cantinflas spouted a rabid and simplistic anticommunism while calling fervidly for free enterprise—and offering himself as the most cogent and apparent example of what hard work can do for one.

Even if on one hand Cantinflas lost touch with his slum roots as he became a multimillionaire with five homes, a thousand-acre ranch, and his own airplane, he at the same time freely donated his time and money to philanthropic causes, appearing at numerous benefits each year and, notably, at one time financially supporting more than 250 poor families in a Mexico City slum. In the end Cantinflas was, justifiably or not, a hero to the Mexican masses, evidenced by the thousands of people who gathered outside the funeral home where his body lay, in tribute to his great talent for making people laugh as well as his enormous generosity.

—John Mraz, updated by David E. Salamie

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: